Training an RNN without Supervision¶

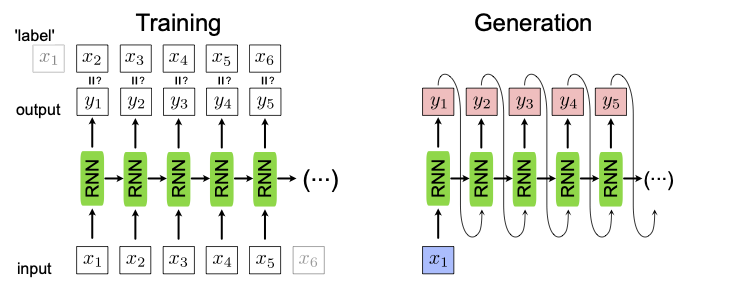

In Sec. Computational neurons, the RNN was introduced as a classification model. Instead of classifying sequences of data, such as time series, the RNN can also be trained to generate valid sequences itself. Given the RNN introduced in Sec. Recurrent neural networks, the implementation of such a generator is straight-forward and does not require a new architecture. The main difference is that the output \(\mathbf{y}_t\) of the network given the data point \(\mathbf{x}_t\) is a guess of the subsequent data point \(\mathbf{x}_{t+1}\) instead of the class to which the whole sequence belongs to. This means in particular that the input and output size are now the same. For training this network, we can once again use the cross-entropy or (negative) log-likelihood as a loss function,

where \(\mathbf{x}_{t+1}\) is now the ‘label’ for the input \(\mathbf{x}_{t}\) and \(\mathbf{y}_{t}\) is the output of the network and \(t\) runs over the input sequence with length \(m\). This training is schematically shown in Fig. 24.

For generating a new sequence, it is enough to have one single input point \(\mathbf{x}_1\) to start the sequence. Note that since we now can start with a single data point \(\mathbf{x}_1\) and generate a whole sequence of data points \(\{\mathbf{y}_t\}\), this mode of using an RNN is referred to as one-to-many. This sequence generation is shown in Fig. 24, left.

Fig. 24 RNN used as a generator. For training, left, the input data shifted by one, \(\mathbf{x}_{t+1}\), are used as the label. For the generation of new sequences, right, we input a single data point \(\mathbf{x}_1\) and the RNN uses the recurrent steps to generate a new sequence.¶

Example: generating molecules with an RNN¶

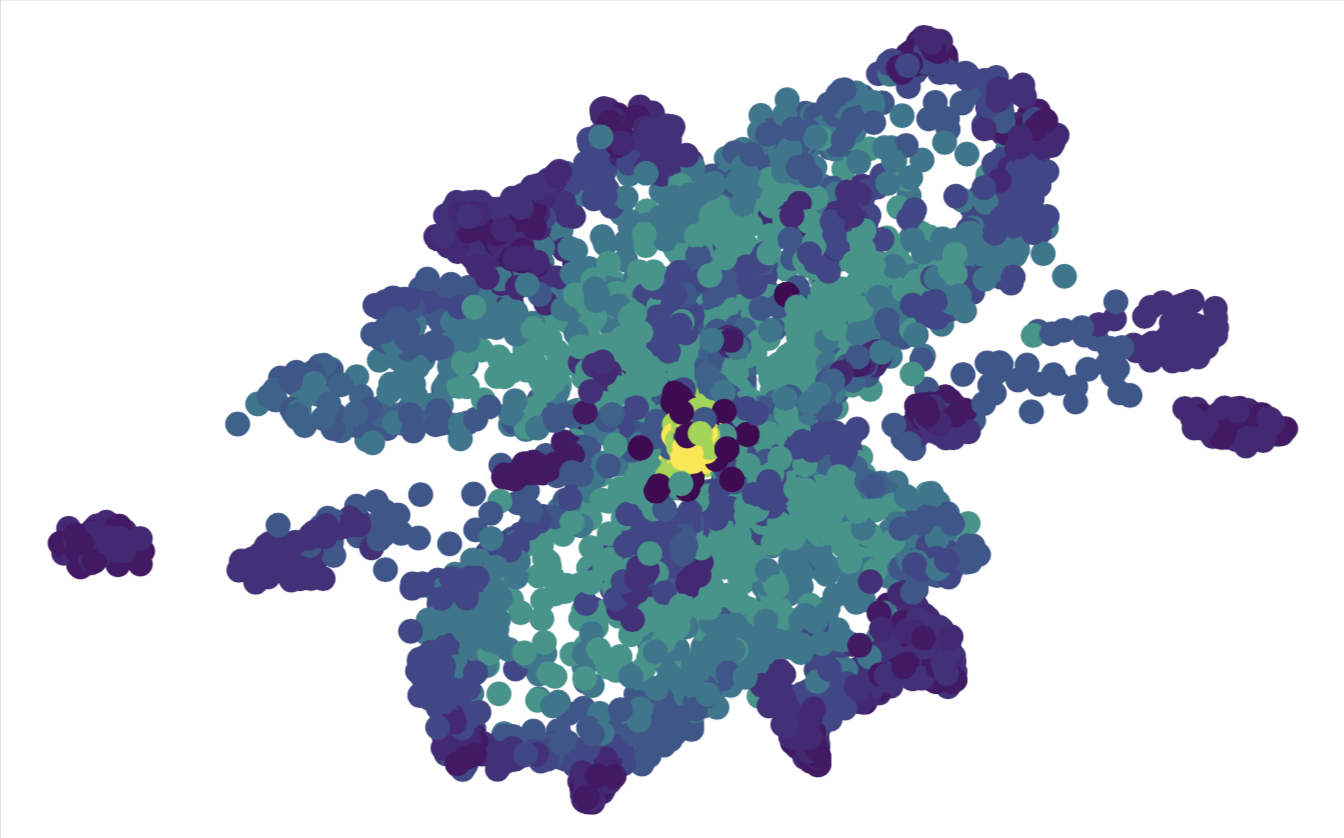

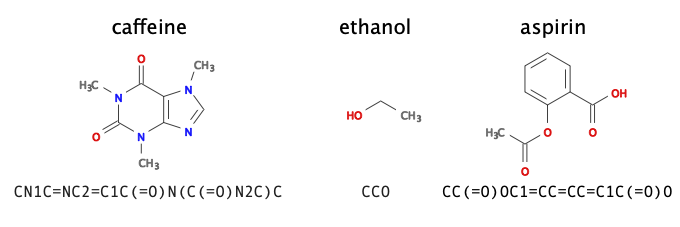

To illustrate the concept of sequence generation using recurrent neural networks, we use an RNN to generate new molecules. The first question we need to address is how to encode a chemical structure into input data—of sequential form no less—that a machine learning model can read. A common representation of molecular graphs used in chemistry is the simplified molecular-input line-entry system, or SMILES. Fig. 25 shows examples of such SMILES strings for the caffeine, ethanol, and aspirin molecules. We can use the dataset Molecular Sets 2, which contains \(\sim 1.9\)M molecules written in the SMILES format.

Using the SMILES dataset, we create a dictionary to translate each character that appears in the dataset into an integer. We further use one-hot-encoding to feed each character separately to the RNN. This creates a map from characters in SMILES strings onto an array of numbers. Finally, in order to account for the variable size of the molecules and hence, the variable length of the strings, we can introduce a ‘stop’ character such that the network learns and later generates sequences of arbitrary length.

We are now ready to use the SMILES strings for training our network as described above, where the input is a one-hot-encoded vector and the output is again a vector of the same size. Note, however, that similar to a classification task, the output vector is a probability distribution over the characters the network believes could come next. Unlike a classification task, where we consider the largest output the best guess of the network, here we sample in each step from the probability distribution \(\mathbf{y}_t\) to again have a one-hot-encoded vector for the input of the next step.

Fig. 25 SMILES. Examples of molecules and their representation in SMILES.¶