Training¶

Adjusting all the weights and biases to achieve the task given using data samples \(\mathcal{D}= \{({\boldsymbol{x}}_1,{\boldsymbol{y}}_1),\dots, ({\boldsymbol{x}}_m,{\boldsymbol{y}}_m)\}\) constitutes the training of the network. In other words, the training is the process that makes the network an approximation to the mathematical function \({\boldsymbol{F}}({\boldsymbol{x}}) = {\boldsymbol{y}}\) that we want it to represent. Since each neuron has its own bias and weights, a potentially huge number of variatonial parameters, and we will need to adjust all of them.

We have already seen in the previous chapter how one in principle trains a variational function. For the purpose of learning, we introduce a loss function \(L(W,B)\), which characterizes how well the network is doing at predicting the correct output for each input. The loss function now depends, through the neural network, on all the weights and biases that we collectively denote by the vectors \(W\) and \(B\).

The choice of loss function may strongly impact the efficiency of the training and is based on heuristics (as was the case with the choice of activation functions). In the previous chapter, we already encountered one loss function, the mean square error

Here, \(||{\boldsymbol{a}}||_2=\sqrt{\sum_i a_i^2}\) is the \(L2\) norm and thus, this loss function is also referred to as \(L2\) loss. An advantage of the L2 loss is that it is a smooth function of the variational parameters. Another natural loss function is the mean absolute error, which is given by

where \(||{\boldsymbol{a}}||_1 = \sum_i |a_i|\) denotes the \(L1\) norm. This loss function is thus also called the \(L1\) loss. Note that the \(L2\) norm, given the squares, puts more weight on outliers than the \(L1\) loss. The two loss functions introduced so far are the most common loss functions for networks providing a continuous output. For discrete classification problems, a great choice is the cross-entropy between true label, \({\boldsymbol{y}}_i\) and the network output, \({\boldsymbol{F}}({\boldsymbol{x}}_i)\) defined as

where the logarithm is taken element-wise. This loss function is also called negative log likelihood. It is here written for outputs that lie between 0 and 1, as is the case when the activation function of the last layer of the network is sigmoid \(\sigma(z)=1/(1+e^{-z})\). (The cross-entropy is preferably combined with sigmoid activation in the last layer.)

Of these loss functions the cross entropy is probably the least intuitive one. We want to understand what it means and gain some intuition about it. The different cost functions actually differ by the speed of the learning process. The learning rate is largely determined by the partial derivatives of the cost function \(\partial L/\partial \theta\). Slow learning appears when these derivatives become small. Let us consider the toy example of a single neuron with sigmoid activation \(F(x)=\sigma(wx+b)\) and a single input-output pair \(\{x,y\}=\{1,0\}\). Then the quadratic cost function has derivatives

We observe that this derivative gets very small for \(\sigma(w+b)\to 1\), because \(\sigma'\) gets very small in that limit. Therefore, a slowdown of learning appears. This slowdown is also observed in more complex neural networks with L2 loss, we considered the simple case here only to be able to say something analytically.

Given this observation, we want to see whether the cross entropy can improve the situation. We again compute the derivative of the cost function with respect to the weights for a single term in the sum and a network that is composed of a single sigmoid and a general input-output pair \(\{x,y\}\)

where in the last step we used that \(\sigma'(z)=\sigma(z)[1-\sigma(z)]\). This is a much better result than what we got for the L2 loss. The learning rate is here directly proportional to the error between data point and prediction \([\sigma(wx+b)-y]\). The mathematical reason for this change is that \(\sigma'(z)\) cancels out due to this specific form of the cross entropy. A similar expression holds true for the derivative with respect to \(b\),

In fact, if we insisted that we want the very intuitive form of Eqs (37) and (36) for the gradients, we can derive the cost function for the sigmoid activation function to be the cross-entropy. This follows simply because

and \(F'=F(1-F)\) for the sigmoid activation, which, in comparison to (36) , yields \(\frac{\partial L}{\partial F}=\frac{F-y}{F(1-F)},\) which, when integrated with respect to \(F\), gives exactly the cross-entropy (up to a constant). We can thus, starting from Eqs. (36) and (37), think of the choice of cost functions as a backward engineering. Following this logic, we can think of other pairs of final layer activations and cost functions that may work well together.

What happens if we change the activation function in the last layer from sigmoid to softmax? For the loss function, we consider just the first term in the cross entropy for the shortness of presentation (for softmax, this form is appropriate, as compared to a sigmoid activation)

where again the logarithm is taken element-wise. For concreteness, let us look at one-hot encoded classification problem. Then, all \({\boldsymbol{y}}_i\) labels are vectors with exactly one entry “1”. Let that entry have index \(n_i\) in the vector. The loss function then reads

Due to the properties of the softmax, \( F_{n_i}({\boldsymbol{x}}_i)\) is always \(\leq 1\), so that loss function is minimized, if it approaches 1, the value of the label. For the gradients, we obtain

We observe that again, the gradient has a similar favorable structure to the previous case, in that it is linearly dependent on the error that the network makes. (The same can be found for the derivatives with respect to the weights.)

Once we have defined a loss function, we also already understand how to train the network: we need to minimize \(L(\theta)\) with respect to \(W\) and \(B\). However, \(L\) is typically a high-dimensional function and may have many nearly degenerate minima. Unlike in the previous chapter, finding the loss function’s absolute minimum exactly is typically intractable analytically and may come at prohibitive costs computationally. The practical goal is therefore rather to find a “good” instead than the absolute minimum through training. Having found such “good” values for \(W,B\), the network can then be applied on previously unseen data.

It remains to be explained how to minimize the loss function. Here, we employ an iterative method called gradient descent. Intuitively, the method corresponds to “walking down the hill” in our many parameter landscape until we reach a (local) minimum. For this purpose, we use the (discrete) derivative of the cost function to update all the weights and biases incrementally and search for the minimum of the function via tiny steps on the many-dimensional surface. More specifically, we can update all weights and biases in each step as

The variable \(\eta\), also referred to as learning rate, specifies the size of step we use to walk the landscape—if it is too small in the beginning, we might get stuck in a local minimum early on, while for too large \(\eta\) we might never find a minimum. The learning rate is a hyperparameter of the training algorithm. Note that gradient descent is just a discrete many-variable version of the analytical search for extrema which we know from calculus: An extremum is characterized by vanishing derivatives in all directions, which results in convergence in the gradient descent algorithm outlined above.

While the process of optimizing the many variables of the loss function is mathematically straightforward to understand, it presents a significant numerical challenge: For each variational parameter, for instance a weight in the \(k\)-th layer \(W_{ij}^{[k]}\), the partial derivative \(\partial L/ \partial W_{ij}^{[k]}\) has to be computed. And this has to be done each time the network is evaluated for a new dataset during training. Naively, one could assume that the whole network has to be evaluated each time. Luckily there is an algorithm that allows for an efficient and parallel computation of all derivatives – it is known as backpropagation. The algorithm derives directly from the chain rule of differentiation for nested functions and is based on two observations:

The loss function is a function of the neural network \(F({\boldsymbol{x}})\), that is \(L \equiv L(F)\).

To determine the derivatives in layer \(k\) only the derivatives of the following layer, given as Jacobi matrix

\[D{\boldsymbol{f}}^{[l]}({\boldsymbol{z}}^{[l-1]}) = \partial {\boldsymbol{f}}^{[l]}/\partial {\boldsymbol{z}}^{[l-1]},\]with \(l>k\) and \(z^{[l-1]}\) the output of the previous layer, as well as

\[\begin{split}\frac{\partial {\boldsymbol{z}}^{[k]} }{ \partial \theta_\alpha^{[k]}} = \frac{\partial {\boldsymbol{g}}^{[k]}}{\partial q_i^{[k]}} \frac{{\partial q_i^{[k]}}}{\partial\theta_\alpha} = \begin{cases} \frac{\partial {\boldsymbol{g}}^{[k]}}{\partial q_i^{[k]}} z^{[k-1]}_j&\theta_\alpha=W_{ij} \\ \frac{\partial {\boldsymbol{g}}^{[k]}}{\partial q_i^{[k]}} &\theta_\alpha=b_{i} \end{cases}\end{split}\]

are required. The derivatives \({\boldsymbol{z}}^{[l]}\) are the same for all parameters.

The calculation of the Jacobi matrix thus has to be performed only once for every update. In contrast to the evaluation of the network itself, which is propagating forward, (output of layer \(n\) is input to layer \(n+1\)), we find that a change in the Output propagates backwards though the network. Hence the name3.

The full algorithm looks then as follows:

Backpropagation

Input: Loss function \(L\) that in turn depends on the neural network, which is parametrized by weights and biases, summarized as \(\theta=\{W,b\}\)

Output: Partial derivatives \(\partial L / \partial \theta^{[n]}_{\alpha}\) with respect to all parameters \(\theta^{[n]}\) of all layers \(k=1\dots n\).

Calculate the derivatives with respect to the parameters of the output layer: \(\partial L / \partial W^{[n]}_{ij} = ({\boldsymbol{\nabla}} L)^T \frac{\partial {\boldsymbol{g}}^{[n]}}{\partial q_i^{[n]}} z^{[n-1]}_j \), \(\quad\partial L / \partial b^{[n]}_{i} = ({\boldsymbol{\nabla}} L)^T \frac{\partial {\boldsymbol{g}}^{[n]}}{\partial q_i^{[n]}}\)

for \(k = 1, ..., n\) do Calculate the Jacobi matrices for layer \(k\): \(D{g}^{[k]}=(\partial {g}^{[k]}/\partial {q}^{[k]})\) and \(D{f}^{[k]}=(\partial {f}^{[k]}/\partial {z}^{[k-1]})\); Multiply all following Jacobi matrices to obtain the derivatives of layer \(k\): \(\partial L / \partial \theta^{[k]}_{\alpha} = (\nabla L)^T D{f}^{[n]}\cdots D{f}^{[k+1]}D{g}^{[k]} (\partial {q}^{[k]}/\partial \theta^{[k]}_\alpha)\)

A remaining question is when to actually perform updates to the network parameters. One possibility would be to perform the above procedure for each training data individually. Another extreme is to use all the training data available and perform the update with an averaged derivative. Not surprisingly, the answer lies somewhere in the middle: Often, we do not present training data to the network one item at the time, but the full training data is divided into co-called batches, a group of training data that is fed into the network together. Chances are the weights and biases can be adjusted better if the network is presented with more information in each training step. However, the price to pay for larger batches is a higher computational cost. Therefore, the batch size can greatly impact the efficiency of training. The random partitioning of the training data into batches is kept for a certain number of iterations, before a new partitioning is chosen. The consecutive iterations carried out with a chosen set of batches constitute a training epoch.

Simple example: MNIST¶

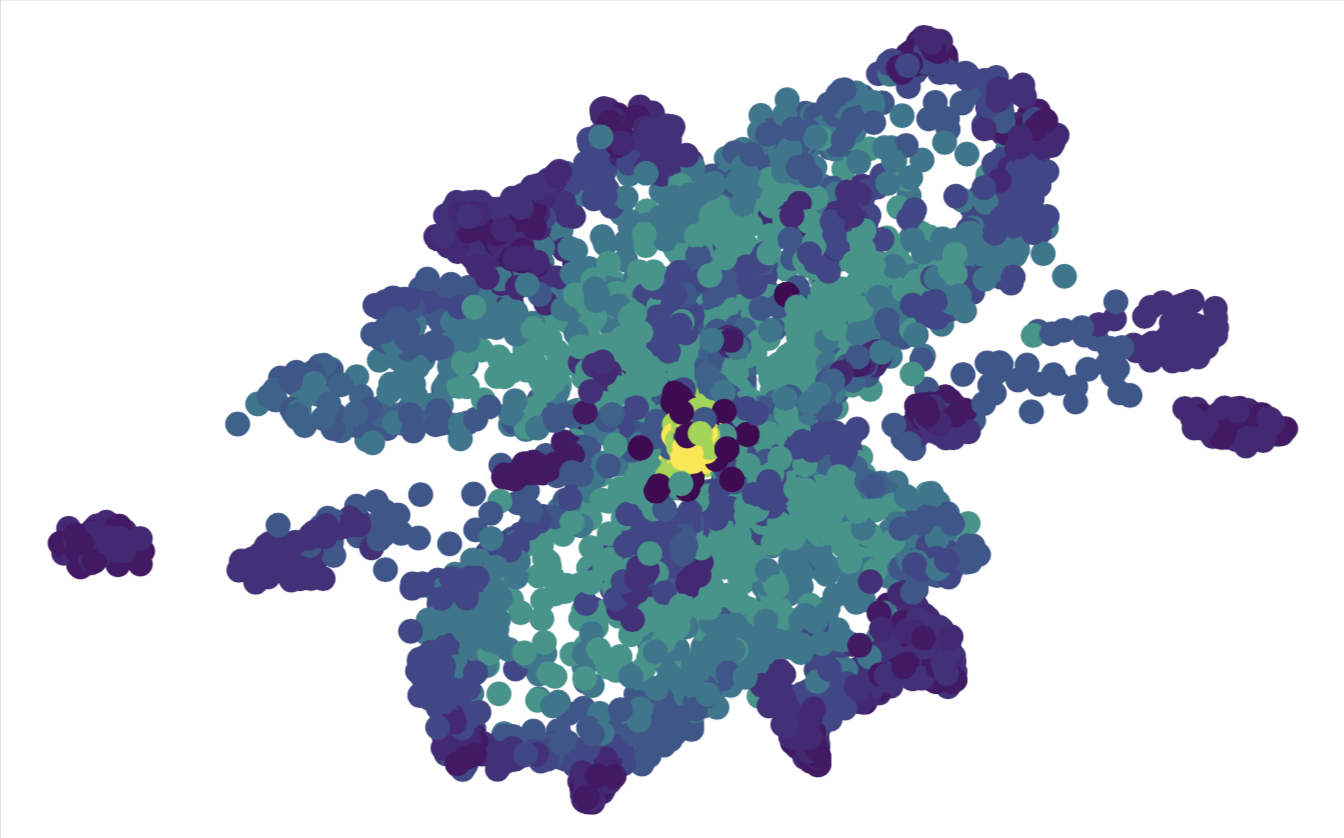

As we discussed in the introduction, the recognition of hand-written digits \(0\), \(1\), \(\ldots 9\) is the “Drosophila” of machine learning with neural networks. There is a dataset with tens of thousands of examples of hand-written digits, the so-called MNIST data set. Each data sample in the MNIST dataset, a \(28\times28\) grayscale image, comes with a label, which holds the information which digit is stored in the image. The difficulty of learning to recognize the digits is that handwriting styles are incredibly personal and different people will write the digit “4” slightly differently. It would be very challenging to hardcode all the criteria to recognize “4” and not confuse it with, say, a “9”.

We can use a simple neural network as introduced earlier in the chapter to tackle this complex task. We will use a network as shown in Fig. 14 and given in Eq. (34) to do just that. The input is the image of the handwritten digit, transformed into a \(k=28^2\) long vector, the hidden layer contains \(l\) neurons and the output layer has \(p=10\) neurons, each corresponding to one digit in the one-hot encoding. The output is then a probability distribution over these 10 neurons that will determine which digit the network identifies.

As an exercise, we build a neural network according to these guidelines and train it. How exactly one writes the code depends on the library of choice , but the generic structure will be the following:

MNIST

Import the data: The MNIST database is available for download at http://yann.lecun.com/exdb/mnist/

Define the model:

Input layer: \(28^2=784\) neurons (the greyscale value of each pixel of the image, normalized to a value in \([0,1)\), is one component of the input vector).

Fully connected hidden layer: Here one can experiment, starting from as few as 10 neurons. The use of a sigmoid activation function is recommended, but others can in principle be used.

Output layer: Use 10 neurons, one for each digit. The proper activation function for this classification task is, as discussed, a softmax function.

Choose the loss function: Since we are dealing with a classification task, we use the cross-entropy, Eq. (35).

Train and evaluate the model: Follow the standard machine-learning workflow to train4 and evaluate the model. However, unlike in the regression example of the previous chapter, where we evaluated the model using the mean square error, here we are rather interested in the accuracy of our prediction.

With the training completed, we want to understand how well the final model performs in recognizing handwritten digits. For that, we introduce the accuracy defined by

If we use 30 hidden neurons, set the learning rate to \(\eta=0.5\) (a mini-batch size of 10 and train for 30 epochs), we obtain an accuracy of 95.49 %. With a quadratic cost we obtain only slightly worse results of 95.42%. For 100 hidden neurons, we obtain 96.82%. That is a considerable improvement over a quadratic cost, where we obtain 96.59%. (Meaning that now about 1 in 14 wrongly classified pictures will now be correctly classified.) Still, these numbers are not even close to state of the art neural network performances. The reason is that we have used the simplest possible all-to-all connected architecture with only one hidden layer. Below, we will introduce more advanced neural network features and show how to increase the performance.

Before doing so, we briefly introduce other important measures used to characterize the performance of specifically binary-classification models in statistics are: precision, specificity and recall. In the language of true (false) positives (negatives) the precision is defined as

Recall (also referred to as sensitivity) is defined as

While recall can be interpreted as true positive rate as it represents the ratio between actual positives and outcomes identified as positive, the specificity is an analogous measures for negatives

Note, however, that these measures can be misleading, in particular when dealing with very unbalanced data sets.

- 3

Backpropagation is actually a special case of a set of techniques known as automatic differentiation (AD). AD makes use of the fact that any computer program can be composed of elementary operations (addition, subtraction, multiplication, division) and elementary functions (\(\sin, \exp, \dots\)). By repeated application of the chain rule, derivatives of arbitrary order can be computed automatically.

- 4

Most ML packages have some type of ’train’ function built in, so no need to worry about implementing back-propagation by hand. All that is needed here is to call the ’train’ function